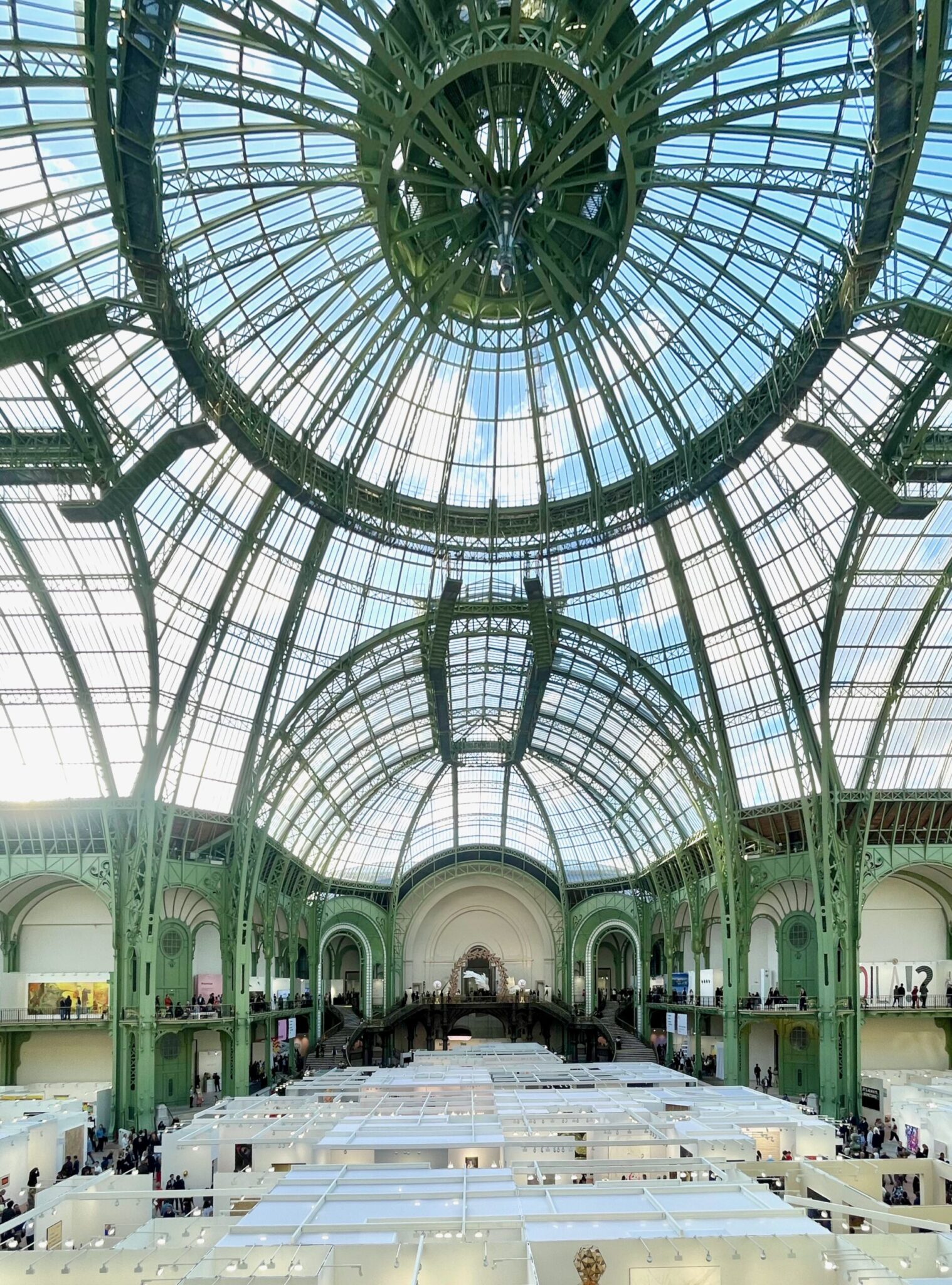

From the moment the doors opened, the Grand Palais resonated with ambition. In 2024, Art Basel Paris made clear that it was not merely a transitional or ancillary fair: it was staking a claim. The renewed architecture, the breadth of galleries, and the curatorial boldness all contributed to a sense that Paris would no longer play second fiddle.

Within the fair, the presentation was both sweeping and intimate. Nearly two hundred galleries from around the world gathered under one roof, with strong participation from French spaces. Among the standout voices were Steffani Jemison, whose subtle sculptural-architectural installation rewrote the boundaries of presence and absence; Carlo Zinelli, via Christian Berst, whose repetitive silhouettes and layered forms drew viewers into meditative reflection; Shahryar Nashat’s Hustler_25.JPEG, where photography, sculpture, and text collided in fragmented narrative; Gerhard Richter at David Zwirner, whose blurred abstractions seemed to breathe in the light of the Grand Palais; and Jean-Marie Appriou, whose hybrid sculptures emerged like mythic futurist beings in dialogue with the space.

Even more charged was the conversation around London. Only days before, Frieze London and Frieze Masters had drawn their global audience to Regent’s Park, along with PAD London anchoring design and decorative arts. London’s fairs had long held sway: vibrant, unpredictable, and commercially potent. But Paris offered something different — a grounding in institutional weight, architectural dignity, and the presence of its own cultural ecosystem. Galleries remarked quietly that while London still had reach, Paris was now commanding symbolism. The rivalry was subtle, but real: between speed and spectacle vs. depth and narrative; between temporary tents and monumental spaces.

Supporting that vision was the Centre Pompidou’s presentation of the Prix Marcel Duchamp 2024 nominees. The shortlist—Abdelkader Benchamma, Gaëlle Choisne, Angela Detanico & Rafael Lain, and Noémie Goudal — was displayed in Galerie 4 at the Pompidou, creating a powerful institutional anchor that paralleled the fair. ADIAF+3centrepompidou.fr+3artreview.com+3 The linkage between fair and museum felt deliberate and potent: Paris was weaving together market and canon, commerce and curation, in one week.

Beyond the Grand Palais, the Hors les murs program extended the fair into urban tissues. Carsten Höller’s giant mushrooms at Place Vendôme, interventions in Palais d’Iéna and Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, and site-specific works scattered through Paris invited all—from collectors to passersby—into the conversation. It was a reminder that the fair wasn’t merely located in Paris, it was Paris.

In the end, Art Basel Paris 2024 confirmed what many had quietly suspected: the French capital was no longer content with resurgence. It is repositioning itself at the core of the contemporary art world. Day by day, artist by artist, institutional voice by institutional voice, Paris reclaimed presence, not just in rivalry with London but on its own terms.

Interview with Abdelkader Benchamma

For AZAP Magazine at Templon Gallery Booth

Q1. Your drawings often create immersive environments that oscillate between the microscopic and the cosmic. How do you balance scientific inspiration with intuitive mark-making?

A: My work often begins with research in areas such as astrophysics, geology, or cosmology. These fields provide images and structures that fascinate me, but drawing itself is an intuitive act. I use scientific ideas as coordinates, but the drawing traces an open journey between them — unstable, unpredictable, and constantly shifting. This balance allows both rigor and freedom to coexist on the page or wall.

Q2. Many of your works invite viewers into states of uncertainty or instability. What role does ambiguity play in your artistic process?

A: I see ambiguity as a vital element rather than a lack of clarity. When a drawing destabilizes perception, it opens up new possibilities of understanding. Ambiguity keeps the work alive: it resists a single reading and instead generates multiple interpretations. For me, that openness is what gives the drawing its energy and its capacity to surprise both myself and the viewer.

Q3. Looking at today’s art world, where does drawing stand for you — as an autonomous practice, a conceptual tool, or a space for experimentation?

A: For me, drawing is all of those at once. It is an autonomous practice with its own history and power, but it is also a laboratory of ideas. The immediacy of drawing — the way a line can shift from intimate detail to monumental form — makes it uniquely versatile. In a world overloaded with digital images, drawing remains one of the most direct and physical ways to think, to imagine, and to question the world around us.